Decentralization & scalability

Table of Contents

What does it mean to be decentralized?⌗

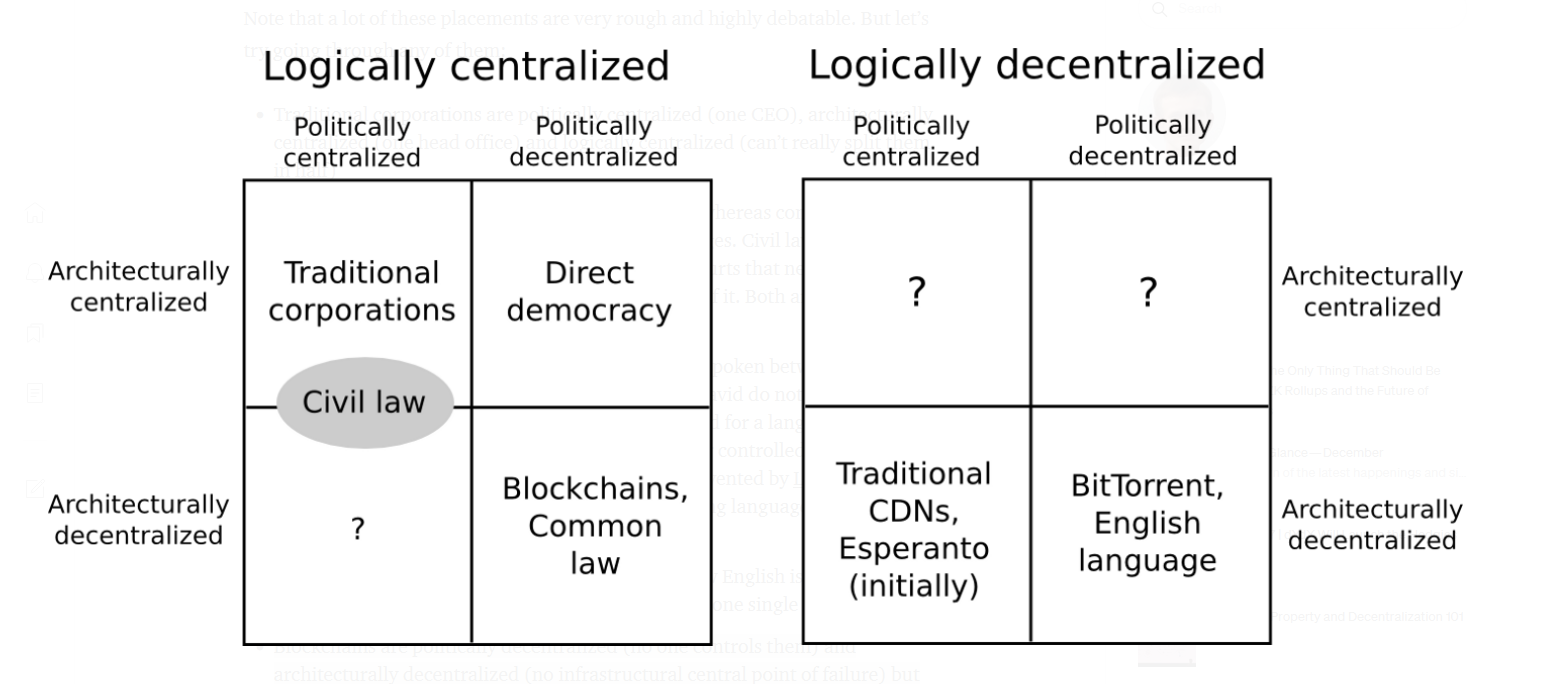

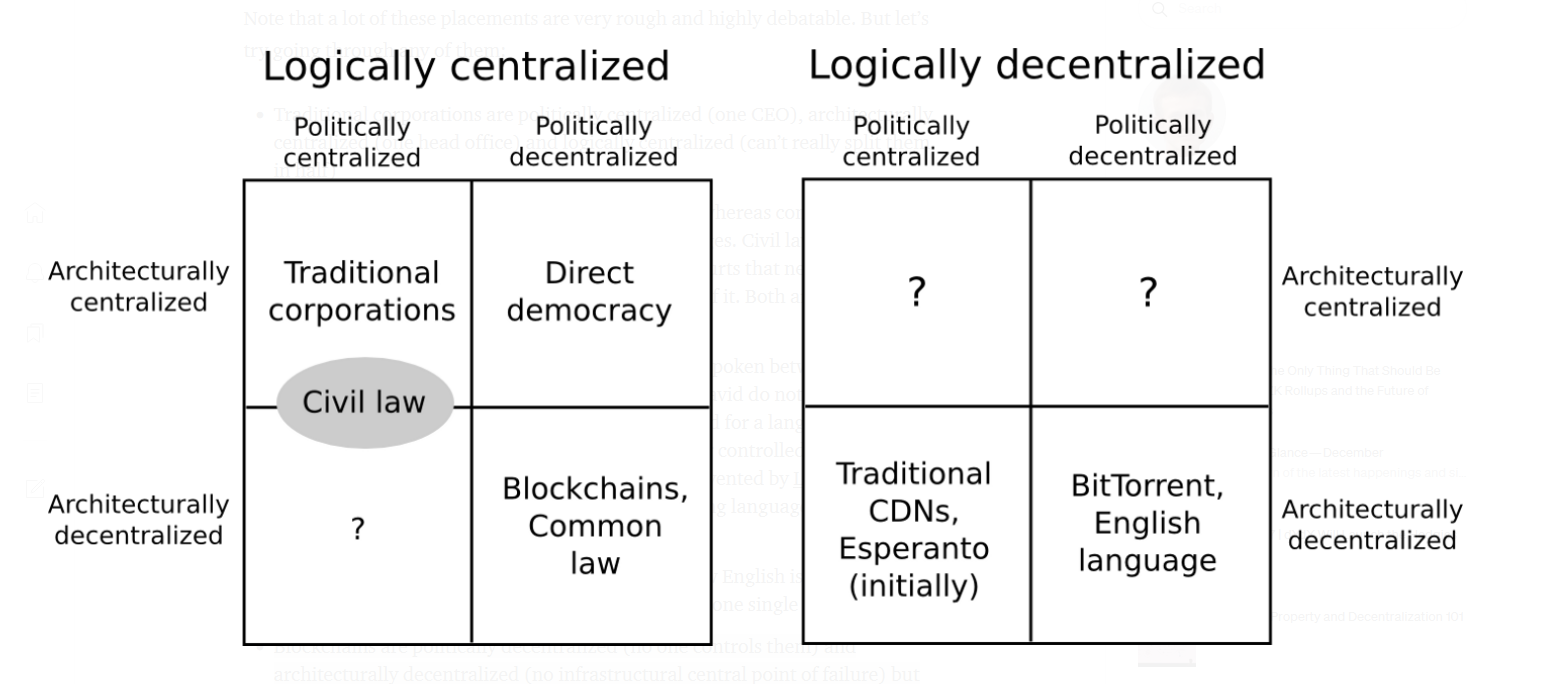

There are three separate axes of decentralization:

- Architectural decentralization – how many physical computers is a system made up of? How many of those computers can it tolerate breaking down at any single time?

- Political decentralization – how many individuals or organizations ultimately control the computers that the system is made up of?

- Logical decentralization – does the interface and data structures that the system presents and maintains look more like a single monolithic object, or an amorphous swarm? One simple heuristic: if you cut the system in half, including both providers and users, will both halves continue to fully operate as independent units?

Blockchains are politically decentralized (no one controls them) and architecturally decentralized (no infrastructural central point of failure) but logically centralized (common agreed state that behaves like a single computer).

Logical centralization is in many cases good, but logical decentralization is good at surviving network partitions.

Architectural centralization can lead to political centralization.

Architectural but non political decentralization could happen when a community uses a centralized forum for convenience but if the owners of the forum act maliciously then everyone will move to a different forum (e.g. cryptotwitter).

Logical centralization makes architectural decentralization harder, but not impossible — see decentralized consensus networks.

Logical centralization makes political decentralization harder, where you can’t simply “live and let live” — see the Block size limit controversy and the DAO fork.

Reasons for decentralization⌗

- Fault tolerance — decentralized systems are less likely to fail accidentally because they rely on many separate components that are not likely to fail in the same way. It’s important to avoid common mode failures, by having different client softwares by different teams, democratized protocol upgrades, geographically sparse nodes and a sparse distribution of coins in a proof of stake blockchain.

- Attack resistance — decentralized systems are more expensive to attack because they lack sensitive central points. Proof of stake is harder to attack than proof of work because hardware is easy to detect, regulate or attack whereas coins can be much more easily hidden.

- Collusion resistance — it is much harder for participants in decentralized systems to collude to act in ways that benefit them at the expense of others. It is important to note that “collusion” simply means “coordination that we don’t like”. It is difficult to have “good coordination” while preventing “bad coordination”.

Blockchain decentralization: what is a node?⌗

A node is a software that participates in the distributed network that makes up a blockchain.

What makes a blockchain trustless is that everyone who runs a node can independently verify the validity of the transactions and verify blocks against consensus rules. If you’re not running a node yourself, you’re trusting someone else to provide you with the correct data (e.g. your MetaMask default provider, Infura).

There are three types of nodes:

- Full nodes — nodes that download and verify block headers (containing the hash of the previous block, the state root, the transactions root, the block number, the timestamp and other info) as well as the list of transactions, verifying that each transaction is valid according to some transaction validity rules. This usually implies having to execute every transaction one by one. A full node stores full blockchain data.

- Light nodes — nodes that only download block headers and assume that the list of transactions are valid according to the transaction validity rules. Light clients only verify blocks against the consensus rules. They store only the header chain.

- Archive nodes — nodes that store everything kept in a full node and build an archive of historical states. Needed if you want to query something like an account balance at block #4,000,000. They’re usually useful for services like block explorers, wallet vendors and chain analytics.

What does it mean to scale a blockchain?⌗

How many units of computation can be processed per block (block size) and how fast a new block may be added (block time) determine the throughput of a blockchain.

To have a high architectural decentralization, it is important to keep the cost to run a node as low as possible to enable as many individuals as possible to participate in the system. The cost is determined by the hardware, bandwith and storage. Note that if the state grows in time, the storage cost grows too, as well as the time of the worst-case execution.

It is also important to keep the time to sync a full node low, because it can prevent certain users to participate in the network. Bitcoin takes 3 hours to sync 12+ years of data, Ethereum about a week for 6 years of data, BSC takes 13 days for 6 months of data, EOS weeks/months, for Solana is impossible, you need to get a snapshot from Solana Labs.

Scalability in the context of blockchains only makes sense when it means more transactions for the same hardware.

Simply increasing the block size or shortening the block time is not a scalability solution since it requires higher hardware requirements, decreasing decentralization.

An example of a scalability solution are validity proofs: a validity rollup (or ZK rollup) moves computation and state storage off-chain but keeps a small amount of data on-chain. Rollups transactions are computed by a Prover, which computes the new state root and a validity proof which mathematically proves the correctness of the execution, and sends them to an on-chain smart contract called Verifier, which verifies the validity proof and updates the state of the rollup to the new one. The key aspect is that the computational cost of verifying the proof is much smaller than executing the underlying transactions. This compression trick proves that the throughput can be increased without increasing the hardware requirements.

In traditional blockchains, the more transactions happen, the more expensive it gets to get a transaction included. With rollups the dynamic is reversed, where the more transaction it gets the less each costs. But this is a story for another article about rollups.