Data Availability: Transaction Data vs State Diffs

Table of Contents

What is Data Availability?⌗

When a new block is added to the Ethereum blockchain, a state root and a transactions root inside the block header are proposed to the network. The state root represents the output of the block’s execution, specifically the state of the Ethereum Virtual Machine after all transactions in the block have been executed.

Full nodes verify the correctness of this state root by locally executing the block’s transactions, or in other words by calculating the new state and comparing it with the proposed state root. If a transaction is missing, the state root (or the transactions root) will differ from the one calculated by the full node, causing the block to be rejected. This mechanism ensures all the data needed to construct and verify the blockchain’s correctness is available.

Rollup bridges, particularly the L2-to-L1 side, are smart contracts that implement a trust-minimized rollup light node on L1. These bridges do not directly execute each state transition to verify correctness; instead, they rely on other methods like fault proofs or validity proofs to verify state roots posted by the rollup’s Proposers.

Proofs are created by rollup full nodes that keep track of the rollup’s state. If the data needed to construct this state is unavailable, it becomes impossible to create such proofs. Unavailable data results in a safety failure in optimistic rollups and in a liveness failure in validity rollups, where safety is guaranteed by validity proofs. Rollups, by definition, publish all the data needed to construct the rollup’s state on the L1 chain in the form of transactions data or state differences between blocks.

Optimistic and Validity constraints⌗

Both transaction data and state diffs are adequate for constructing the rollup’s state, but the mechanism used for proofs can impact data availability requirements. In a validity rollup, full nodes verify the state root using validity proofs, so they don’t need to execute the transactions that result in the corresponding state. This means that validity rollups can be flexible regarding the data they publish on L1, whether it be transaction data (i.e. the input of the validity proof) or state diffs (i.e. the output). As of the time of writing, zkSync Era, Starknet and rollups based on StarkEx publish state diffs, while Polygon zkEVM and Scroll publish transaction data.

Optimistic rollups on the other hand need to check the state root validity by executing each transaction, so they are constrained to publish transaction data.

Transaction history⌗

State diffs enable more cost-effective transactions compared to full transaction data because they can omit signatures and when multiple transactions modify the same slots, only the final state is published, allowing for better cost amortization. A direct consequence of this is that such rollups do not ensure the availability of the complete transaction history. While this is ideal for rollups like dYdX to conceal other users' trades, it can negatively impact the user experience for others by making block explorers less reliable, especially with decentralized sequencers. A transactions root can be used to verify the inclusion of certain transactions, but this mechanism does not help with data withholding. For example, Starknet has no plan to ensure the availability of the complete transaction history.

Finality⌗

Posting transaction data offers better finality guarantees to full nodes. When transaction data reaches L1, full nodes can independently verify its receipt by executing it within its sequencing window. In contrast, the outcome of a transaction in a rollup with state diffs can only be determined after a validity proof related to it is published. Since validity proofs are expensive to verify and are more cost-effective when batching lots of transactions, they are posted less frequently than what is possible with transaction data, leading to longer finality times.

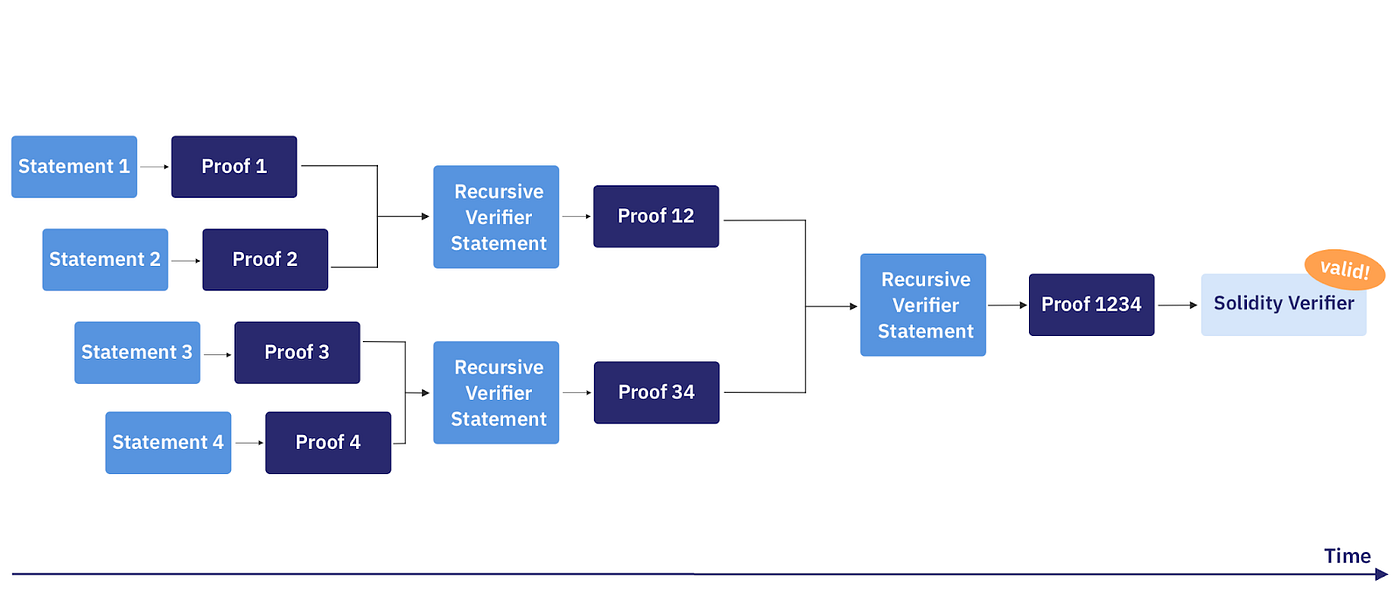

A solution discussed by Sovereign Labs consists in creating proofs using recursive proving and sharing them over the p2p network: first prove single transactions upon arrival, and then aggregate these proofs into other proofs in a tree structure. Since only the last aggregated proof is posted on-chain, this method achieves faster finality without paying extra for on-chain verification. With this method the bridge is no longer the source of truth for nodes (even light clients), turning the rollup into a sovereign chain. Another approach is to publish these proofs on-chain but without verifying them.

For more information, see Starknet Decentralized Protocol V - Checkpoints for Fast Finality.

Forced inclusions (L1->L2 messages)⌗

Posting transaction data makes it easier for L1-to-L2 messages to be force included in the rollup in the case of an offline or censoring sequencer because they’re similar in nature. For example, by specification Optimism Bedrock requires the first block in a rollup epoch to include all the transactions submitted via L1. Arbitrum uses the Delayed Inbox for forced transactions that can be moved to the Core Inbox (which is what defines what is included in the rollup) after a sufficient amount of time has passed, currently 24 hours.

For state diffs based rollups, since a transaction needs first to be executed with its output published on-chain, it cannot be easily included without a sequencer and a prover. StarkEx chains allow users to submit transactions directly on L1, but the “forcing” consists in applying a penalty, usually the halt of the chain, if they are not included withing a predefined time window. zkSync Era plans to introduce a mechanism called Priority mode, where anyone can become an operator if L1 requests are not being processed. Starknet currently has no mechanism to force inclusions but it’s being discussed. It’s important to note that, except for Priority mode, in this type of rollups forcing is just a threat to the rollup’s liveness and not an actual method to automatically include transactions, like it is with transaction data based rollups.

Polygon zkEVM is the first validity rollup live on mainnet that employs transaction data. Proofs must reference sequenced batches, and users can submit forced batches among them. Both sequenced and forced batches are used as inputs for validity proofs. Since proofs are only used for the bridge and batches are what define the rollup’s state, transactions can be forced into the rollup even without a prover.

Forced exits (L2->L1 messages)⌗

L2-to-L1 messages are used to exit the rollup and to transfer assets out of the bridge. Withdrawals are initiated on L2 and finalized on L1 by providing an inclusion proof to the corresponding state root. The data needed to construct the proof is guaranteed to be available by the data posted on-chain. In the case of no new state roots being published, a user can propose blocks (eventually with proofs) autonomously, or refer to the last published one.

There are no particular differences between transaction data and state diffs based rollups in this regard.